A Sign from the Heavens — Tattoos of the Japanese Phoenix

The phoenixes in these traditional Japanese tattoos don’t need to rise from their own ashes to maintain immortality.

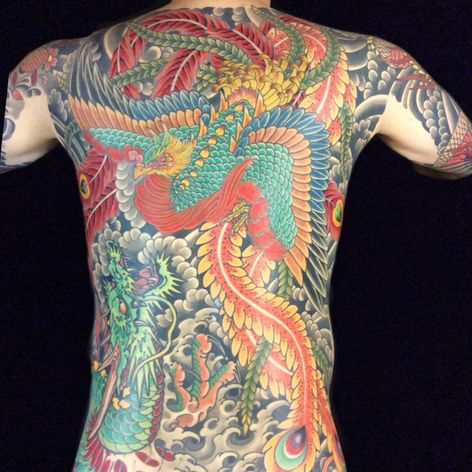

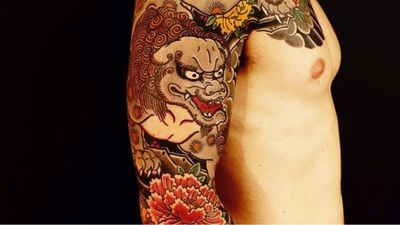

Phoenixes in Irezumi aren’t anything like the phoenixes that most people are familiar with. They’re not made of fire, they don’t rise from their own ashes, and they certainly don’t flock with birds of a fiery feather. In fact, they really aren’t phoenixes at all (that’s just what they’re commonly mistaken for, because of their slight resemblance to the Western archetype of immortal avian life); they’re actually known as hou-ou, and they have been around far longer than their incendiary doppelgängers. Have a look at these back-pieces and sleeves, and you’ll start to see what sets the hou-ou apart from other mythological creatures.

Like most of the mythical figures found in Irezumi, the hou-ou migrated to Japan from China, where it’s known as the fenghuang (“hou-ou” is derived from the sound of the Japanese pronunciation of this Chinese term). The two are, for the most part, identical, but Japanese artists have taken artistic liberties over the centuries, changing some of its features to resemble birds that are native to the country, such as the blue magpie or red-crowned crane, and surrounding it with indigenous plants like peonies and paulownia trees, to make it their own.

According to legend, if a hou-ou descends from the heavens, it’s a sign of peaceful times to come, but when it returns to its celestial abode, trouble’s on its way. Beyond its status as a double-edged omen, the hou-ou can also be read as the the physical manifestation of the marriage of masculine and feminine energy, aka yin and yang. This is because, centuries ago, the Chinese phoenixes were thought to be gendered. Over time, the two were conflated into a singular female entity because hou-ou were often paired with dragons (like in back-pieces by Henning Jorgensen and Luca Ortis), which are traditionally seen as male.

The hou-ou has appeared in many examples of Eastern art over the centuries, perched on top of the famous Byōdō-in temple in the Kyoto Prefecture, and spreading its wings in the ukiyo-e (woodblock prints) from the Edo period by masters like Kuniyoshi and Hokusai. Today, however, its main roost is in traditional Japanese tattoos. Tattooists who specialize in this style are keeping the Japanese phoenix alive, and because of it and the bird’s auspiciousness, Irezumi will always have a bright future ahead of it.

To see more traditional Japanese tattoos of mythological creatures, pay these artists’ Instagrams a visit. If you want a hou-ou of your own, have one of them create a depiction of the legendary bird on your body.

You’ve just experienced Indomitable, our series where we examine the meaning behind our favorite motifs from traditional Japanese tattoos. We hope you liked learning about about the hou-ou, aka the phoenix of the East. While you’re at it, check out our previous posts about cherry blossoms, dragons, hannya masks, kirins, kitsune, the Nue, samurai crabs, and tofu boys.