Sacred Rites: Preserving Indigenous Tattoos

Summary

Skin stitching, Aboriginal tattoos, and Inuit tattoos have become popular again, but two artists speak on why they don't belong to everyone.

The beauty of Indigenous Canadian and Native American culture has, for centuries, been deprecated, stolen, and stifled. Each tribe has had to overcome mass genocide, “re-education”, as well as forced separation from tribal rites and rituals. And although many people would like to think of this as “ancient history”, it’s very clearly not. Currently, each clan within the Wet’suwet’en Nation, along with thousands of supporters, have been blockading a natural gas line that cuts through their unceded territory. Elizabeth Warren recently made headlines for insisting on Native American heritage, sparking more debates on cultural appropriation, among other things, while in many reservations around the Northern Hemisphere, highly intense numbers of Native women are slaughtered with very little governmental concern or help.

But beneath the consistent turmoil, there is hope. Many people like Cheyenne Randall, Alethea Arnaquq-Baril, as well as charity events such as the yearly Warriors Fund, are steady voices of support amidst the perpetual flow of heartbreaking news. There are also artists, like Maya Sialuk Jacobsen and Dion Kaszas, who are working diligently to preserve important tattoo techniques deeply embedded within Indigenous culture, not only in an effort to protest the contemporary standing of their people but to also reconnect with what was stolen from them. These tattoo techniques are symbolic of what generations have lost, but also proof of Indigenous perseverance. As Dion puts it, “My existence is a testament to the strength and resilience of my ancestors, whose tears, prayers, and blood paid the price for me to do the work that I do today. The revival of my ancestral tattooing practice is a gift from the creator and one of my responsibilities to the people to be.”

A Missing Piece of the History of Tattoos:

The Disappearance of Native American tattoos and Aboriginal Tattoos

The interest in skin stitching, Inuit face tattoos or other aboriginal tattoos may stem from immediate novelty, but one has to understand that part of the reason why these tattoo techniques seem “new” are because they were suppressed by colonialism. Maya explains, “The tattooing was banned or at least frowned upon by the missionaries that followed the colonization of our lands. It took 50-80 years to lose the practice. With the practice also the technique of skin stitching vanished. Inuit lands are vast and stretches from Chukotka, Alaska, Canada to and including Greenland. We are a widespread people and the circumstances of colonization were not the same everywhere. Some areas have not tattooed for 250 years; others lost the practice in the 1930s. But we all did stop skin stitching at some point.”

Dion also helps to pinpoint some of the many reasons why Indigenous culture was eradicated, “The Nlaka’pamux ancestral embodied artistic practice of tattooing was put to sleep for a period of around 150 years, the reason for this is the story of colonization on Turtle Island...The fabric of our cultures and tattooing practices began to ever so slightly fray at the edges, the moment the first boat containing Judeo-Christian ‘explorers’ caught sight of Turtle Island. In the blinking of a crusty sea weary eye we were reduced to heathens and savages not worthy of our lands and sovereignty, through the racist discriminatory legal construction of the Doctrine of Discovery...Diseases, Indian Agents, government officials and missionaries had already attacked the threads of our existence for one hundred and forty-six years by 1831, when the Mohawk Indian residential school was opened in Brantford Ontario. The residential school system cut to the core of Indigenous existence, our children. It forcibly removed children from families and communities and sometimes moved them across the country in an effort to civilize them.” With their children stolen, the future generation’s knowledge and preservation of unique cultural aspects was almost lost. But Dion and Maya are perfect embodiments of those who reconnected with sacred rites.

An Intimate Connection to Skin Stitching and Inuit Tattoos:

These Tattoo Techniques are Part of a Personal Journey

The history of tattoos has spanned nearly every geolocation and culture around the globe for millennia, but there are certainly differences in the importance of the tattoo practice to each set of peoples. For Maya, her connection comes through the generations that came before her, bestowing a powerful heritage she keeps safe-guarded. “I am Greenlandic Inuk and a trained tattooer with 20 years of experience. I have learned and worked with several tattoo techniques. The one closest to my heart is skin stitching as it is the way that my foremothers tattooed. As our foremothers were extremely skilled in sewing fur and skins as it was key to survival in the Arctic, it is not strange that it was the technique of choice when they were tattooing...Skinstitching is by far the most difficult way of tattooing that I have tried. Difficult in the sense that it is harder to control the outcome. It is a very important cultural tradition amongst Inuit women and it is part of what divides us from the usual story told about Inuit in the Arctic. A story that has focused on the hunting skills and survival skills of the Inuk man. I am thrilled that there is more focus on the female technology of arctic survival.” In Maya's Instagram posts she often asks that those who are enamored with these designs to be mindful of using them, "Please respect our patterns. Inuit kalaallit still needs time to reconnect to our old ways of marking our skin. We need our patterns to stay intact. Our patterns are deeply rooted in our spirit belief system and we use them today to rebuild identity after 300 years of colonization."

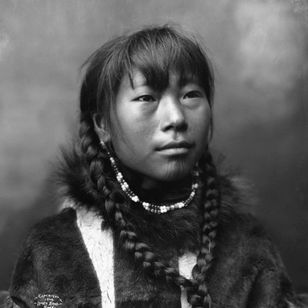

Traditional Inuit tattoos by Maya Sialuk Jacobsen #MayaSialukJacobsen #aboriginaltattoos #indigenoustattoo #inuittattoo #skinstitching #historyoftattoos #culturalpreservation

Dion, too, feels this inextricable link to the ancestors, “There are many sacred aspects to Indigenous peoples tattooing practices and the symbolism associated with these traditions. In many cases, these aspects are unique to each individual's journey and story. Each Indigenous culture, nation, community, family and individual has their own journey with the symbols and practice. For some nations, the designs and motifs, are inherited and accompany names which stretch back to an original ancestor and each time the name is given and its accompanying tattoo applied it is a reincarnation of the original ancestor. Sometimes our tattoos are given in dreams by our spirit helpers, sometimes given for healing for physical, emotional and spiritual trauma. Today I would argue that Indigenous tattoos include all the aforementioned aspects but also are an embodiment of our ancestor’s resilience, strength, and prayers.”

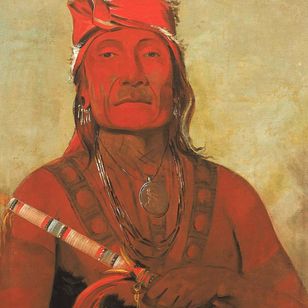

Hand poke traditional indigenous tattoo by Dion Kaszas #DionKaszas #handpoke #indigenoustattoo #historyoftattoos #culturalpreservation

The Symbolism of Skin Stitching and Aboriginal Tattoos:

Why an Inuit Face Tattoo is May Not Be Yours to Wear

The intimate aspect of tattooing for these particular cultures makes speaking on specific symbolism difficult. Maya was kind enough to give a brief overview of some important aspects of this practice. “Again we are widespread people and there are variations. Generally, though tattooing and thus skin stitching was a part of our old religion. In Canada and Greenland, the patterns are hunting-related amulets that the woman has tattooed in her skin with needle and thread. A man wore loose amulets in his clothing and on his hunting gear. The tattooed amulets protected and provided. In Alaska and Chukotka, the tattoos are also religious but rather than creating hope for future hunting results, the tattoos tell about former hunting results. They also describe world view. The difference between the two is the phase of religion.”

However, Dion points out that sharing special information in hopes of preservation or education can be detrimental. “It would be inappropriate for me to give further in-depth explanations concerning the sacred aspects at this time, far too often the generosity of Indigenous peoples to share intimate, sacred aspects of our cultures and ancestral practices have resulted in the appropriation and misappropriation of that knowledge for the gratification and financial gain of those who wish to use things that they do not have rights, relationship or responsibility to.”

The Issue of Cultural Appropriation in Tattoo Practice:

Skin Stitching, Native American Tattoos, and Aboriginal Tattoos are Sacred

Cultural appropriation is certainly not a new concept, nor is it something that will very soon see its end. Maya isn’t really worried about the techniques being stolen; she explains that skin stitching won’t exactly resonate with Westerners who prefer the trends of perfectionist Fineline or lavish Neo-Traditional. “I doubt that skin stitching would ever become more than a fad in Western tattooing. This is because of the lack of control and the simplicity of tattooing that is possible to do by skin stitching. I worry more about the patterns, to be honest. I keep my tattoo work away from Instagram where there are very many Western tattooers. I don’t attend tattoo conventions, I don’t tattoo outside of Inuit areas: mainly I work in Greenland and Denmark where there is a huge population of Greenlandic Inuit. I work slowly with releasing patterns and information from my 10 years of research to avoid feeding the first craze of revival that spreads into Western tattooing. That is how I try and avoid cultural appropriation.”

Illustration of Inuit Facial Tattoos from Dion Kaszas's Indigenous Tattoo Site - please respect these sacred tattoos - #DionKaszas #inuitfacetattoo #inuittattoo #handpoke #indigenoustattoo #historyoftattoos #culturalpreservation

Technique based fears are something Dion isn’t anxious about either. He says, “The reality is when it comes to technique everyone was handpoking before Edison and Samuel O’Reilly, so poke away. The issue arises when designs, symbols, and sacred aspects of Indigenous peoples communal knowledge is used without rights, relationship, or responsibility. If people wish to embody Indigenous symbols, design styles, and artwork, get tattooed by an Indigenous person who comes from a nation that originally tattooed using those symbols, designs, styles, etc. If this is not possible, commission an Indigenous artist who has rights, relationship, and responsibility to those designs and motifs and have them design a work they feel is appropriate for you to have tattooed by whomever you choose. Wherever your ancestors originate from, dig deep into your place and find inspiration for your own designs, symbols, and motifs. Develop new ceremonies, rituals and practices associated with your ancestral lands and territories, don’t steal ours. Our world will become more beautiful as it is filled with the diversity of designs, symbols, and motifs informed by your ancestry and homelands. It's time to take your hands off our stuff, including unceded territories, design styles, motifs, and sacred knowledge that you don’t know how to take care of.”

Illustration of Inuit Tattoos from Dion Kaszas's Indigenous Tattoo Site - please respect these sacred tattoos - #DionKaszas #inuitfacetattoo #inuittattoo #handpoke #indigenoustattoo #historyoftattoos #culturalpreservation

Ancient History is Still Modern Reality:

The Homes of Indigenous Tattoos and Native American Tattoos Are Still War Torn

Again, while those who are not directly connected to Native American tattoos, Indigenous tattoos, or Inuit tattoos and techniques such as skin stitching, may think that the history of tattoos is rife with free inspiration, there are certain aspects that, while ancient, still reside within the active torture of particular demographics. Dion looks to the current fight in Canada over the corporate hunger for cash clashing with the health of the environment and the people who safeguard that land. “I feel it is important to share that when I consider the sacred aspects of our ancestral tattooing practices, I am reminded of my relatives who are on the frontlines defending our homelands and territories against resource extraction and development. It is in these places that our tattoos speak the loudest to their sacredness and indelible connection to mother earth. With this in mind, I feel it is important to bring to your attention to what is happening right now in so-called British Columbia, Canada. On February 7th, 2020 the Royal Canadian Mounted Police raided Gidimt’en checkpoint on unceded Wet’suwet’en territory. The Wet’suwet’en are an Indigenous nation who has been defending their land from the Coastal GasLink pipeline, which is their right as unceded stewards of their territory. When I use the term unceded what I mean is that the Wet’suwet’en have not given up their territory through treaty, war, or surrender. I ask that you please educate yourself about the Wet’suwet’en’s fight for their land, and a multitude of other similar violations of human rights happening in the nation-state of Canada.”

In the midst of a fraught people who are spread far and wide, coming face to face with an ongoing battle for peace and the freedom to own what is truly theirs, Maya shares her hopes for the future. “My hopes and dreams are that all Inuit tattooers will work from a place of knowledge about the practice and the religion that it is part of. That our communities can be offered tattooing that belongs to their clans and tribes because knowledge would ensure that Inuit tattooing is no longer treated as a homogenous mass of patterns for a homogenous mass of people. We are so many tribes and subtribes and each has their way of putting the patterns together. My hopes and dreams are for a tattooing practice that is healthy, safe and culturally sound. With knowledge, the ritualistic aspects come all by itself. We have to realize that ethnicity is simply not enough of a demand to be a traditional practitioner.”

Photograph of a group with Inuit Facial Tattoos from Dion Kaszas's Indigenous Tattoo Site - please respect these sacred tattoos - #DionKaszas #handpoke #indigenoustattoo #historyoftattoos #culturalpreservation

And for those who are still drawn to the use of sacred Native American tattoos or Aboriginal tattoos such as skin stitching or tapping without a true thread of connection, Dion’s advice is to not only dig deep into your own culture to make symbols or rituals that are authentic to you but to also stand with a people who are consistently attacked through philosophical or physical force, “The reason our tattoos are so sacred is because they connect us to our lands and territories and they speak of our responsibilities to that land. If you really want to respect and honor our tattoos and if you really want to feel connected to our symbols: research, spread the word and stand with us against the consumption, exploitation, and extraction of our communal heritage, including our lands, territories, symbols, ceremonies and cultural practices.”

From Maya's IG: "Today we got interviewed at Greenlandic Broadcasting together with this amazing warrior Aaju Peter. #kakkiornerit #kalaallitnunaat #inuitcultureandtradition #inuitattootradition #greenlandicwomen "